Mauro Hayes Peter The Art of Americanization at the Carlisle Indian School Pdf

1. Introduction

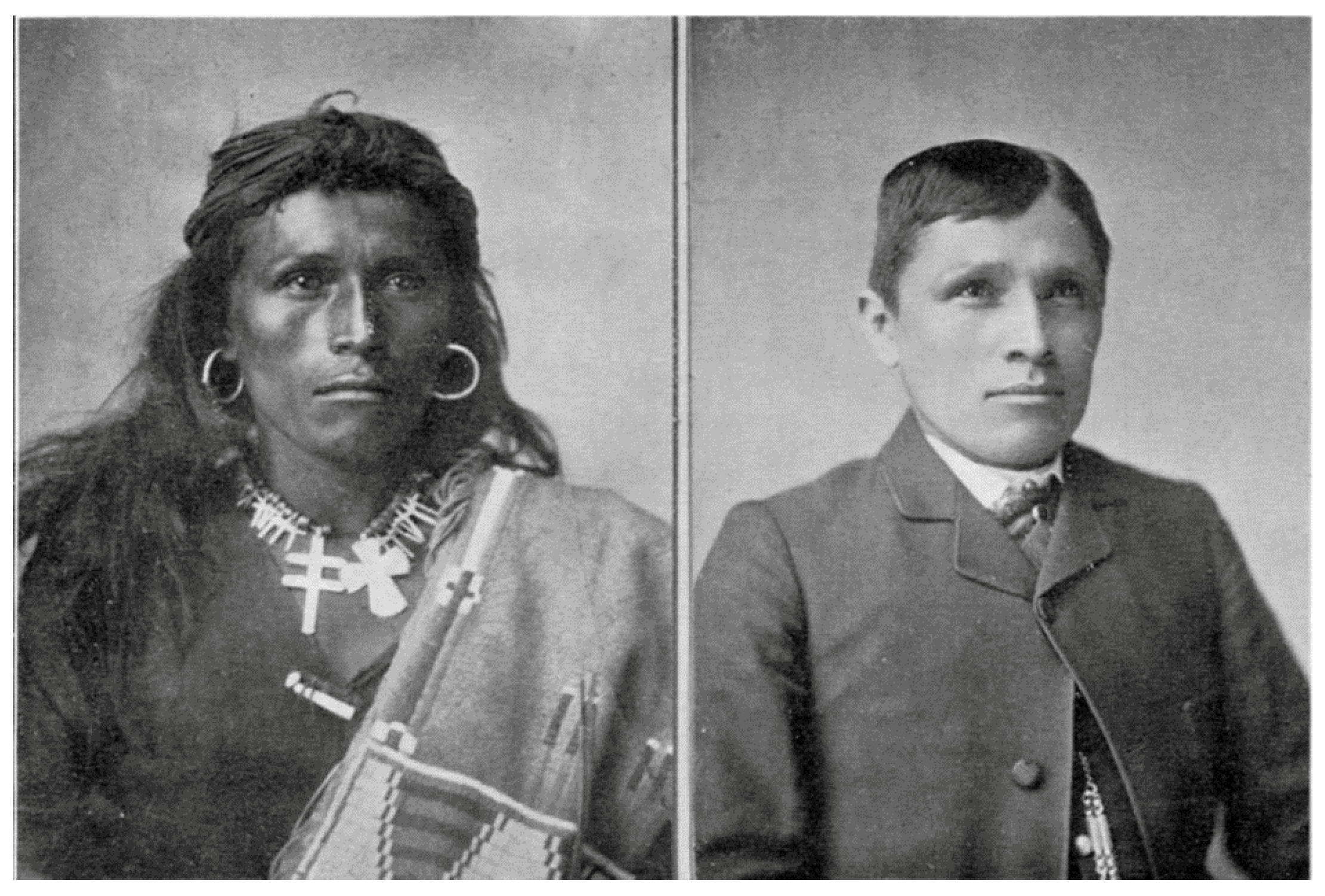

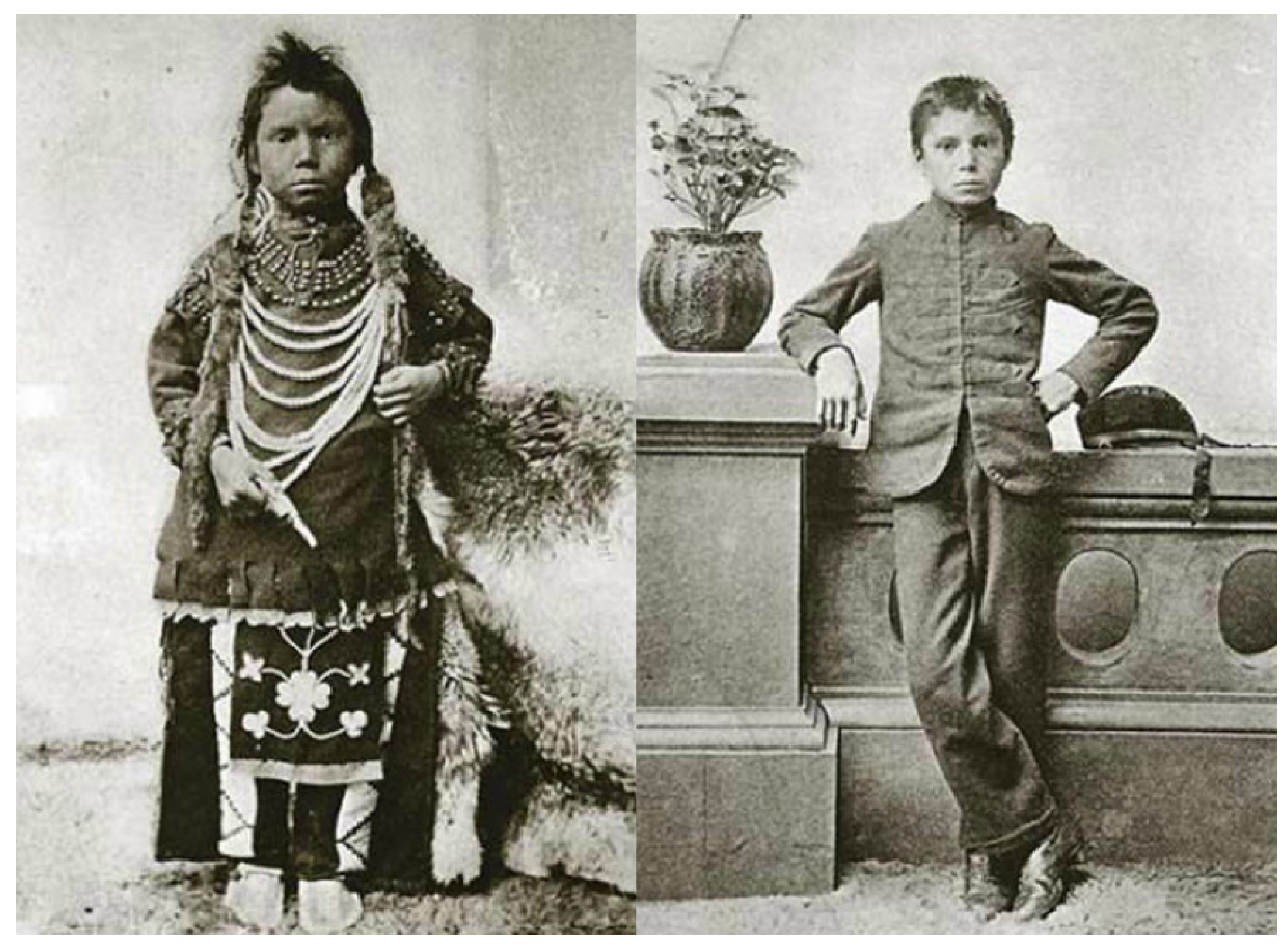

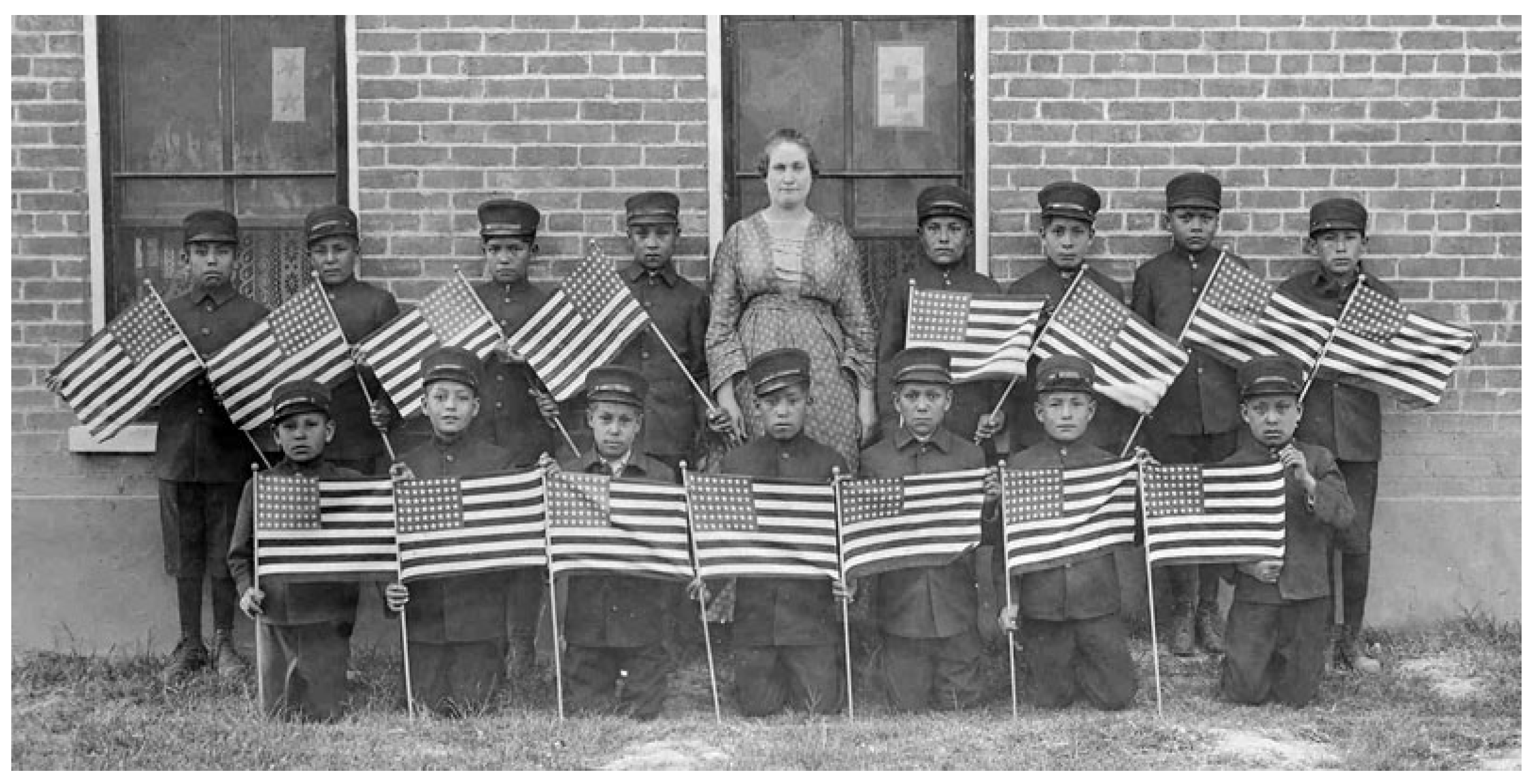

Mortiferous diseases, forced separation from family unit, exhaustive manual labor, military marches, and inferior curriculum feature prominently in the common perception of the American Indian boarding school experience at the plow of the twentieth century. Official school photographs have been used to illustrate these harsh conditions of assimilation [ane,ii,three,4,5,six,7,8,9,10,eleven,12,13,14,fifteen,sixteen,17].one Images of Native students in armed forces dress staring vacantly at the camera are indeed persuasive in casting indigenous youths every bit victims of state-sponsored oppression. Created well-nigh notably by the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania [two,xiii], merely also by other Indian schools across the Us and Canada, the photographs frequently depict students "before-and-after" entering school or otherwise engaged "civilizing" activities (Figure 1, Effigy 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Effigy one. Tom Torlino—Navajo, "As he entered the school in 1882" and "As he appeared 3 years later" from Souvenir of the Carlisle Indian Schoolhouse, 1902. Courtesy of the Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Middle.

Figure one. Tom Torlino—Navajo, "As he entered the school in 1882" and "Equally he appeared three years subsequently" from Souvenir of the Carlisle Indian School, 1902. Courtesy of the Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center.

Figure 2. Thomas Moore before and afterwards admission to Regina Indian Industrial School, ca. 1897. Saskatchewan Athenaeum Board (R-A82223 1-ii).

Figure ii. Thomas Moore before and later admission to Regina Indian Industrial School, ca. 1897. Saskatchewan Archives Board (R-A82223 1-2).

Effigy 3. Indian boarding schoolhouse at Cantonment, Oklahoma, ca. 1909. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (Neg. no. LC-USZ62-126134).

Figure 3. Indian boarding schoolhouse at Cantonment, Oklahoma, ca. 1909. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (Neg. no. LC-USZ62-126134).

Figure iv. Albuquerque Indian Schoolhouse, ca. 1895. National Archives at Denver (NAID 292873).

Effigy 4. Albuquerque Indian School, ca. 1895. National Athenaeum at Denver (NAID 292873).

During the forced assimilation era, between 1870 and 1930, countless numbers of these images were created and circulated.two As visual sociologist Eric Margolis notes, these photographs "conformed to established conventions of centre-class portraiture, thus reinforcing the predominately Anglo viewers' perception that a 'civilizing procedure' was being documented" ([3], p. 78). In improver to Margolis, other scholars take examined these schoolhouse-produced images as "powerful vehicles of credo" ([18], p. ane) and as the "fine art of Americanization" [13] but, thus far, there has not been an analysis of the pupil-produced photographs, nor of the images that they collected of their own school experiences.

Using a group of photographs collected and created past Parker McKenzie (Kiowa) and his classmates while attending both Rainy Mount and Phoenix Indian Schools, this paper intends to rectify that oversight through a reading of these snapshots as examples of visual sovereignty. Visual sovereignty, originally coined by (Seminole-Muscogee-Diné) photographer Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie, describes Native photographic self-representation and the (re)claiming of ethnic identities in club to counter colonial imagery that has dominated the archives. She calls this "compensating imbalances", where "an imbalance of information is presented as truth. No longer is the photographic camera held by an outsider looking in, the camera is held with brown hands opening familiar worlds. We document ourselves with a humanizing heart, [and] we create new visions with ease…" ([nineteen], p. 29). An examination of McKenzie's images provides a first-hand account of the educational institutions that afflicted the lives of so many American Indians during the first one-half of the twentieth century. The results of this examination challenge the prevailing treatment of the subject in suggesting that the official schoolhouse photographs are not the well-nigh representative visual record of American Indian boarding school experiences. As Don Alexander stated, "Native people live in a prison of images not of their own making" ([20], p. 45).

The student-produced photographs portray a much different story than those found in almost boarding school collections. In these images, students picture themselves every bit active participants in a changing modern earth, not the passive victims often described and depicted in conventional narratives. This is not to say that these photographs are the only records of students' experiences. In fact, over the last thirty years scholars have extensively documented the Native point-of-view through diaries, personal correspondence, and interviews with quondam boarding school students [6,eleven,15,xvi,21,22,23,24,25,26]. Through these histories, we accept learned that their experiences were much more nuanced than previously described. Some students enjoyed aspects of their time at the boarding schools, which included playing sports, meeting new friends, and learning new skills. While the oral histories now tell a different story, the visual history all the same reflects the assimilationist propaganda for the schools. As Tsinhnahjinnie argues,

Native people, photographed dramatically in advisable cruel attire, vanishing before ane'south eyes. Native people photographed in suits of assimilation tailored to the correct perspective of a progressive new world. Such schizophrenia lamented the disappearing of the "Indian" and all the same celebrated images of "Indians" accepting progress. That which could not be scrubbed with soap and water, dressed properly, beaten or destined for extinction was and is the persistence of the indigenous soul, persistence to exist the force of endurance…There is no doubt in my mind that the people imaged in these photographs are aware of the integral link they take to today'southward beingness.

([27], pp. 43–44)

Rather than depicting the relentless regimentation and systematic extirpation of Native cultures, the visual record presented by students points to a sure degree of autonomy that immune for the development of fraternal bonds and pride (both for their civilisation and their schoolhouse). Every bit a whole, the student snapshots requite usa a glimpse into the identity formation and transformation that occurred inside Indian boarding schools during the first decades of the twentieth century.

Photographic Sources

According to the Oxford Companion to Photographs, "by 1906, photography was existence taught to students at Carlisle Indian School in ane of the finest and best equipped photography studios in the state of Pennsylvania" ([28], p. 437). Presumably, there would be several examples of student work produced in this studio. Yet, only one student has been identified every bit a lensman at Carlisle—John Leslie (Pullyap)—and he attended more than decade before the studio was completed. On 1 June 1894, Carlisle's schoolhouse newspaper, The Indian Helper, described Leslie as the "right hand Indian man" to John Choate, the official school photographer ([29], p. 116). A later outcome advertised the 1895 gift catalog of the school every bit including photographs by Leslie (Figure 5), announcing that, "Think this is Indian work and the commencement sent out from Carlisle school" ([29], p. 118).

Figure 5. "The Subcontract House" photograph by John Leslie (Pullyup) from the Us Indian School, Carlisle Pennsylvania, gift catalog published in 1895.

Figure 5. "The Farm Firm" photograph by John Leslie (Pullyup) from the United States Indian School, Carlisle Pennsylvania, souvenir itemize published in 1895.

However, the photographs in the souvenir catalog are not credited, and some images are considered to be the piece of work of John Choate (per the Cumberland Historical Society). Those photographs that are attributed to Leslie are largely architectural photographs and, as fine art historian Hayes Mauro states, "his images bear a noticeable imprint of Choate's compositional influence" ([thirteen], p. 125). In other words, he was directed to take certain pictures, and did not have much artistic license while practicing photography at school.three For these reasons, I opted not to include the work of John Leslie in this written report.

Although photography was a popular art class that was taught in at least one Indian boarding school, there are relatively few Native-produced photographic collections available to the public. This is probably because these photographs, like most personal photographs, have been retained by the family or tribe of the writer, rather than being accessible in public archives. A useful exception to this pattern is a big photographic collection created by a Kiowa man, Parker McKenzie (1897–1999), which he personally donated to the Oklahoma Historical Social club. McKenzie is perchance best known for his work in recording and preserving the Kiowa linguistic communication, which culminated in 2 publications, Popular Account of the Kiowa Language (1948) and A Grammar of Kiowa (1984). As a immature man, McKenzie attended both an on-reservation boarding school at Rainy Mountain and an off-reservation schoolhouse at Phoenix. His photographic collection provides valuable insights into the early years of the boarding school arrangement and contains photographs taken by himself and his school sweetheart (later his married woman) Nettie Odlety, besides as a small assortment of official school photographs. Information technology is on this collection that this commodity is based. Although there are approximately three hundred photographs in his collection, I selected a small-scale sample of fourteen images by using the post-obit criteria: the reproductive quality of the print, the amount of information written on the verso, the variety of subject matter, and the oral and written documentation provided past Parker McKenzie when he donated the drove to the Oklahoma Historical Society.

ii. Rainy Mountain Boarding School

Parker Paul McKenzie attended Rainy Mountain Boarding School from 1904 to 1914. One of several on-reservation boarding schools established by the federal government, Rainy Mountain was located on the Kiowa-Comanche-Apache Reservation in southwest Oklahoma. Although it was intended to serve the Indian community equally an elementary school (kindergarten to 6th grade), several students enrolled as teenagers. McKenzie noted that "since many started at a late age, they got too old before finishing the available grades" [30]. This explains why the students photographed in the Pie Club (Effigy 6) seem to range in historic period from pre-pubescent to late teens. The image depicts seven girls dressed in aprons and belongings platters of desserts (strangely, none of which announced to be pies) and continuing outside a schoolhouse edifice.

Figure 6. Rainy Mountain Pie Lodge, ca. 1915. Unknown photographer. Parker McKenzie Collection, Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Order.

Figure 6. Rainy Mountain Pie Lodge, ca. 1915. Unknown photographer. Parker McKenzie Drove, Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

The Pie Society is one of the few Rainy Mountain school photographs retained by McKenzie that appears to be taken by an official schoolhouse photographer.4 By the time this photograph was taken (ca. 1915), McKenzie had already avant-garde and transferred out of the school. Notwithstanding he held onto the photograph, and about 70-five years subsequently, he was still able to name all of the people in the photograph: "Left to Right Standing: Nellie Ontowe Komalty, Eunice White Buffalo, [unknown given name] Hootetter, Isabell Due south. Tsatske, Grace Odlepaugh (Doyeto). Front end Row: Carrie Quetowe Sahmaret, Nellie McKenzie (died in 1917)" [photo verso]. As he noted, shortly later this picture was taken, his piddling sis, Nellie, would die of tuberculosis—an unfortunately common disease that plagued boarding schools. McKenzie had very few images of her, and although this is well-nigh likely the reason he kept the photograph, it can be read as much more a wistful keepsake.

"Creating a visual history," states curator Theresa Harlan (Santo Domingo/Jemez Pueblo), "is a question of buying" ([31], p. twenty). By incorporating the Pie Lodge photograph into his personal annal and identifying the figures, McKenzie has finer claimed the picture every bit role of his family album. The image no longer functions as an anonymous grouping portrait like and then many other Indian boarding school photographs take go. This human action of transference is possible because, as aboriginal photographer Michael Aird maintains, indigenous viewers "look by the stereotypical way in which their relatives and ancestors accept been portrayed, considering they are just happy to encounter photographs of people who play a function in their family unit'southward history" ([27], p. 25). Withal, I am non implying that visual sovereignty is enacted exclusively as a mnemonic device for the purposes of nostalgia. Visual sovereignty also gives agency to Native peoples to gainsay decades of not-Native representations. Similar Harlan argues, "we must reject the reduction of Native images to sentimental portraits…this type of thinking reduces Native survival to a matter of nostalgia, and precludes discussion of the political strategies that enabled Native survival" ([31], p. 20).

For some students, surviving the boarding school experience meant taking ownership of their situation—some ran abroad, while others stayed on and carved out a space inside the institution. The Pie Gild image evinces the latter. Baking was non just encouraged, but enforced past the domestic science curriculum that constituted half of the female students' coursework ([8], pp. 136–64). The goal, according to historian Michael Coleman, was the "extirpation of tribal cultures and the transformation of Indian children into most copies of white children...[with] labor appropriate to 'proper' gender roles" ([seven], p. 40). Regardless of the implications of baking as "gendered" work or its Anglo associations, the women pictured in the Pie Club appear to have enjoyed cooking enough to join an extracurricular club. Such concepts of happiness and enjoyment do not usually accompany the descriptions of Indian boarding schoolhouse photographs. If a educatee actually took pleasure in a school activity, then he or she has been seen by some scholars [9,10,32] as a victim of brainwashing. Yet, "sovereignty is the border that shifts indigenous feel from a victimized stance to a strategic one," declares Tuscarora creative person and scholar Jolene Rickard ([31], p. 51). But labeling these students as "victims" does very little to explicate how these people adjusted, endured, and possibly even enjoyed parts of their boarding school experience.

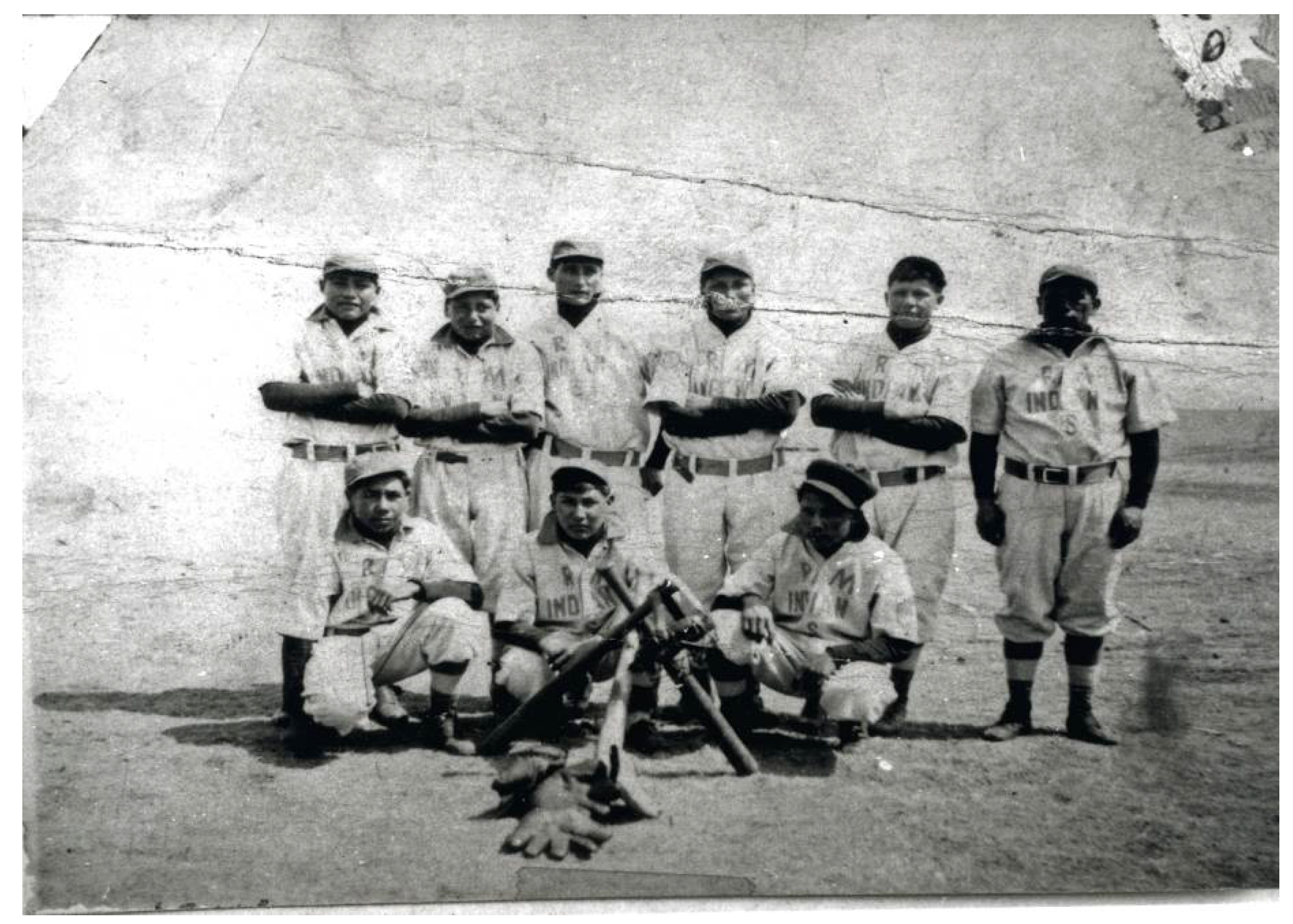

Perhaps the virtually popular action that reportedly brought pleasure to the students was participating in ane of the athletic programs. In a photo titled, "Jump 1913 Brawl Squad" (Figure 7) the 9 members of the Rainy Mount Indian baseball squad are posed in their uniforms for a team moving picture. This is the same year that Jim Thorpe started his major league baseball career. And then, information technology is probable that these players felt immense amount of hope and pride in playing baseball at this particular time.

Figure seven. Rainy Mountain, Bound 1913 Ball Team. 1913. Unknown photographer. Parker McKenzie Collection. Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Figure 7. Rainy Mountain, Jump 1913 Ball Squad. 1913. Unknown lensman. Parker McKenzie Collection. Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

The Ball Squad photograph can also be read every bit just another try by the ascendant, Anglo guild to instill a Western value organisation—one that favors competition, discipline, and winning. However, sports historian John Flower found that "even though mainstream sports were intended to assimilate the Native children and teenagers who attended boarding schools, former students expressed a type of indigenous pride in their memories of sports, a pride that conveyed antiassimilationist sentiments" ([21], p. nineteen). Team photographs, thereby, stand equally visual reminders of the sense of pride and laurels associated with boarding schoolhouse athletics. For instance, when Blossom was collecting oral histories for his book, he noted that participants eagerly requested old photographs of pupil athletes ([21], p. 101). One educatee remembered that, "I was a proficient athlete…I recall in the finish I got the better of that school. I was more of an Indian when I left than when I went in" ([21], p. 980).

As with the Pie Lodge photograph, McKenzie provided a complete list of the subjects: "Left to Right, Forepart Row: Catcher Daniel McKenzie, David Frizzlehead, Leslie Aitson. Continuing: Fred Quoeton, Luis Necone, Andrew Ahhaitty, Jimmie Chanate, Matthew Botowe & Inkonish Henry (a Caddo)" [photo verso]. A common tactic of visual sovereignty is restoring the names and tribal affiliations to the subjects. Creative person and curator Gerald McMaster (Cree/Blackfoot) did the same when he analyzed a Battleford Indian Schoolhouse football squad photograph and granted "the boys the nobility of names…to requite them back their identities" ([33], p. 78). In McKenzie's case, he identified the terminal figure, Inkonish Henry, every bit being "a Caddo"—a tribal nation with roots in East Texas and Oklahoma. He makes tribal designations for almost all of subjects in his photographs (or at to the lowest degree those people whom he could call up); indicating that fifty-fifty though they are part of a team or a school, each person however has their own tribal identity—even if the tribes did not traditionally coexist in a peaceful mode. This tribal integration in the Indian boarding schools led to a type of intertribal identity that fostered a sense of community amidst all students regardless of tribal origins. The manner in which these Pan-Indian students presented themselves was not Western, nor was it traditionally tribal. As Amelia Katanski writes, "through their creativity and their flexible understanding of identity, boarding-school students represented themselves every bit much more than than newspaper Indians or Melt'due south representative Indians, icons of cultural assimilation. Instead, they fashioned a creative infinite for cocky-joint and for complex, syncretic identity formation…" ([6], p. 130). The photographs taken by Parker McKenzie when he transferred to Phoenix Indian School offer some the all-time illustrations of this motility.

iii. Phoenix Indian Schoolhouse

By his ain account, McKenzie did not accept any photographs while at Rainy Mountain. In a letter accompanying his collection he stated:

At Rainy Mountain, we had no knowledge of picture taking with kodaks. On an occasion [sic] Sunday visitors from Gotebo would bear witness and took few pictures of the students. None of the employees or their family members had kodaks, so they were new things to the states when we arrived in Phoenix in September 1914. Nosotros soon learned few of the students were taking pictures and in no time, some of us Okies began the practise, and later "learning the ropes", we were snapping many pictures [34].

Indeed, McKenzie'south photographic collection consists of over three hundred images taken with a Kodak Brownie camera during his schooling at the Phoenix Indian Boarding Schoolhouse. It is phenomenal that McKenzie was able to create so many photographs, since scholars and former students have commented on the military-fashion scheduling that made every moment of a student'south day strictly planned. For case, co-ordinate to historian David Wallace Adams, boarding school life was marked by a "relentless regimentation…nearly every aspect of his 24-hour interval-to-24-hour interval existence—eating, sleeping, working, learning, praying—would exist rigidly scheduled, the hours of the twenty-four hours intermittently punctuated past a seemingly endless number of bugles and bells demanding this or that response" ([viii], p. 117). The official boarding schoolhouse images seem to support this argument and often depict students in class, marching, or doing chores.

Overall, there are relatively few photographs of Native students relaxing during break. McKenzie's drove is an exception to this fact. In one photo, two girls, Nettie Odlety (Kiowa) and Francis Ross (Wichita), lounge on the grass, propped up by their elbows, smile at the camera (Figure viii).

Figure 8. Nettie Odlety and Francis Ross. 1915. Photograph by Parker McKenzie. Parker McKenzie Drove. Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Figure 8. Nettie Odlety and Francis Ross. 1915. Photo by Parker McKenzie. Parker McKenzie Collection. Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Both girls have bows in their hair and appear to be dressed in coincidental, white sundresses. It is an image of relaxed, carefree youth, enjoying their teenage years. With a smile, they welcome the photographer whose calendar is simply to testify his affection past taking a snapshot. Here is that "humanizing eye" as described by Tsinhnahjinnie, and the warmth and intimacy that is just not found in earlier photographs of boarding school students.

In a similar photograph created following year (1916), Doye Cleveland and Nettie Odlety are pictured in their school uniforms seated on the campus grounds (Effigy 9). They appear to be caught in the act of studying, equally at that place are books scattered most them. Once more, Parker McKenzie has found his sweetheart and has persuaded her and her friend to have their motion picture taken. These photographs are just two of the hundreds of images created past McKenzie as he roamed the campus taking pictures of his classmates during suspension. Most of his photographs describe Odlety alone or with classmates, leading us to believe that McKenzie spent most of his breaks seeking out his girlfriend.

Figure 9. Doye Cleveland and Nettie Odlety, 1916. Photograph by Parker McKenzie. Parker McKenzie Collection. Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Figure 9. Doye Cleveland and Nettie Odlety, 1916. Photograph by Parker McKenzie. Parker McKenzie Collection. Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

By enacting visual sovereignty, Parker McKenzie'south photographs reframe the Indian boarding schoolhouse experience, placing the focus on individual experiences and personal relationships rather than sanctioned activities and impersonal forces. Nowhere is this more than apparent than in his photographs featuring his future wife Nettie. 3 years after this photograph (Figure 9) was taken, Parker and Nettie were married. They stayed married for 59 years until her death in 1978 and would eventually accept five children together. Indeed, these photographs certificate the initial stages of an epic love story as shared by its Native author, reflecting the words of Comanche cultural critic and curator Paul Chaat Smith, "our snapshots and home movies create an American epic," ([33], p. 99). Like all classic love stories, this i has a player that attempts to keep the lovers autonomously—the Indian boarding schoolhouse.

Indian boarding schools prohibited physical contact between the sexes as much as possible. Dorms were segregated and assistants kept a watchful eye on the students. Classrooms and mutual areas gave students the opportunity to fraternize and flirt. This was certainly true of the relationship of Parker McKenzie and Nettie Odlety whose relationship began with notes passed in grade, which were written in phonetic Kiowa "to foil our instructor in the event one of our notes fell into her hands" [34]. One photograph shows the couple together on campus, in forepart of the Administration building, dated March 1916 (Figure 10). The administration building, a neutral area (every bit far as proctors are concerned), was the perfect setting for an innocent meeting betwixt schoolhouse sweethearts. They stand in their own space, not touching or fifty-fifty looking at each other—in fact, while Nettie gladly smiles at the photographic camera, Parker looks somewhere off-photographic camera. Their body language seems almost uncomfortable, perhaps shy, every bit they stand stiffly with their easily shoved in their pockets.

Figure 10. Nettie Odlety and Parker McKenzie in front of the Assistants Building, March 1916. Unknown Lensman. Parker McKenzie Collection. Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Social club.

Effigy 10. Nettie Odlety and Parker McKenzie in front of the Administration Building, March 1916. Unknown Photographer. Parker McKenzie Drove. Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Of grade, this could be a reaction to being observed by the faculty—they are, subsequently all, posed straight in front of the administration building. McKenzie complained that, "keeping the sexes apart was routinely strict…we were under strict discipline, we were never free" (as quoted in [22], p. 74). Contrary to this statement, he and Nettie were nonetheless able to create this portrait straight under the commonage noses of the assistants. Anishinaabe scholar Gerald Vizenor would call this a "avoiding pose" ([35], p. vii). It is an embodied act of visual sovereignty, operating in a space of resistance and compliance. Furthermore, this image is probably ane of the only visual examples of an actively courting couple at an Indian boarding school. While there are images of couples at school-sanctioned activities, such as school dances or picnics, at that place are few, if whatsoever, focusing on one specific couple as this image does.

Judging from the casual wearing apparel of Nettie and Parker, the photograph was most likely taken on a Saturday. Saturdays were the one day of the calendar week that students were free to choose their own schedule. They could participate in an extracurricular activity, written report, relax, or sign up for a position with the outing system. The outing system (a type of paid vocational training which was met with mixed reviews) allowed the students to earn some extra spending coin, from $10 to $forty per month ([12], p. 136). Because the time period, this was a lot of money for a teenager, and these students were often the only breadwinners in their household ([12], p. 136). The schoolhouse established cyberbanking accounts for these students so they could salvage, ship the coin back home, or spend it on "town twenty-four hour period." On select Saturdays, students were allowed off-campus to visit the downtown Phoenix area. As Trennert notes, "those with money spent information technology on water ice foam, candy, a flick, or some personal item from a department store; the rest did considerable window shopping" ([12], p. 133). Although he did not specifically mention it, McKenzie most likely had his film developed and purchased new film on these shopping days. Moreover, some of the more stylish hats and dresses tin probably be traced to purchases made on these Saturdays.

The wearable worn on boondocks days is perhaps all-time illustrated in a photograph (Effigy 11) taken past McKenzie quondam between 1914 and 1917. He identifies the 3 classmates pictured as "Easchief Clark (Pro-Wrestler); Ross Shaw, Pima; Andrew Ahhaitty, Kiowa" [photograph verso].

Figure 11. Easchief Clark; Ross Shaw; Andrew Ahhaitty. ca. 1914–1917. Photo by Parker McKenzie. Parker McKenzie Drove. Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Gild.

Figure 11. Easchief Clark; Ross Shaw; Andrew Ahhaitty. ca. 1914–1917. Photograph past Parker McKenzie. Parker McKenzie Collection. Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

The individualized approaches to manner reflected in what nosotros tin assume are the personal wearable of each—the subjects clothing different styles of hat, necktie, shoes, and slacks—stand in stark dissimilarity to the sartorial conformity imposed by the boarding school uniforms. Notwithstanding, for the source of the image, the viewer would exist hard pressed to associate the urbane young men in the picture show with the dull grayness stamp of the Indian boarding schoolhouse. It is quite possible that, in dressing for town days, McKenzie'south classmates were reflecting the influence of a common town day activity—the movies. The fashion choices revealed in the photo call up the expect of Douglas Fairbanks, Charlie Chaplin, and other pop actors of the twenty-four hours. Thus, by appropriating popular trends and actively engaging with mainstream culture, these Native subjects are expressing their visual sovereignty. Moving picture and visual studies scholar Michelle Raheja (Seneca) finds "visual sovereignty as a way of reimagining Native-centered articulations of self-representation and autonomy that engage the powerful ideologies of mass media…" ([36], p. 197). The personalized choices visible in their wardrobes advise that these students are acutely aware of the contemporary identities that they are projecting. They represent a vibrant and contemporary Native culture, dynamically reconfiguring their Native identities and embracing modernity and mainstream civilization on their ain terms. Quite distinct from the hapless figures staring out from backside school uniforms in official boarding school photographs, these young men have donned modern "uniforms" of their own choosing, tailoring their identities in every sense of the give-and-take.

Parker McKenzie not only photographed his friends and sweetheart, but his family besides. One of the primeval photographs that he took at Phoenix was a portrait of his brother, Daniel McKenzie dated to September 1915 (Figure 12). In this image, Daniel is seated behind a desk in the center of his dorm room. Behind him, there is a steel-framed bed, a nightstand with several framed photographs, and a few pennants hanging on the wall. By all indications, the students could decorate their space equally they saw fit.

Figure 12. Daniel McKenzie, Kiowa, September 1915. Parker McKenzie Drove, Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Figure 12. Daniel McKenzie, Kiowa, September 1915. Parker McKenzie Collection, Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Daniel sits facing the viewer with his left arm casually thrown over his chair while his other arm rests on his desk behind a pile of books. He presents himself using the entire setting, every bit Erving Goffman states, "infuses his activity with signs which dramatically highlight and portray confirmatory facts that might otherwise remain unapparent or obscure" ([37], p. 30). In other words, he presents himself every bit a serious student, studying and embracing a new Indian identity. This is not only apparent in his appearance, but in his expression. He appears very confident and self-bodacious, the complete antithesis of typical hollow-eyed educatee pictured in so many of the officially-produced boarding schoolhouse photographs. Here, Daniel's gaze is visually absorbing—it is neither welcoming nor challenging. Like Vizenor writes, "the true stories of pictures are in the eyes…the optics are the tacit presence…the eyes that come across in the aperture are the balls of narratives and a sense of native presence" ([35], p. 7). Native brothers on either side of the lens, co-authoring their visual narrative of boarding school, this is visual sovereignty.

About a year afterward, Parker would be photographed in much the same fashion. In 1916, Parker created one of his many self-portraits that he titled: Parker McKenzie, Kiowa, at Main Edifice (Figure thirteen). In this image, the young Parker, similar his brother before him, is seated at a desk, leaning back, with his left arm resting on his chair. His correct paw, however, is placed atop a typewriter on a desk in front end of him. The entire scene is photographed outdoors, on the grass, with a school edifice in the immediate background.

Figure 13. Parker McKenzie, Kiowa, at Main Building. 1916. Parker McKenzie Drove, Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Order.

Figure 13. Parker McKenzie, Kiowa, at Main Building. 1916. Parker McKenzie Collection, Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Instead of facing the viewer, Parker McKenzie chooses to pose in three-quarter profile, gazing off into the distance. This pose, forth with the hand on the typewriter, recalls images of famous intellectuals and statesmen—as if he is fashioning himself in the canon of traditional Western portraiture. Art historian Richard Brilliant considers that "most portraits exhibit a formal stillness, a heightened degree of cocky-sophistication that responds to the formality of the portrait-making situation" ([38], p. 10). Indeed, McKenzie responds to the act of producing a portrait past forcing a pose and styling himself in the manner of a distinguished scholar. This reading of the epitome may be contested, but it is reinforced past McKenzie's later remark that he "owes much to his early grooming" for becoming a Kiowa scholar and furthering his cultural heritage [34]. Furthermore, he was already thinking about his future as a linguist, when he stated that "the innocent practice [of passing notes written in Kiowa] was beginning to fascinate me if non my partner. Information technology led me to experiment with words and simple expressions for myself and before long saw some words would not yield to English language spelling or be written phonetically with the English language alphabet" [34]. While this prototype foreshadows the subsequently career of McKenzie, what is even more than fascinating is where this scene is photographed—outdoors.

There is evidence that in some years, the boarding schools were overcrowded, but never to the indicate that classes took place exterior. This is why the desk and typewriter are such an enigma in the cocky-portrait of Parker McKenzie. Were the items brought outside for the purpose of staging the photograph? Or were these items already outside considering they were in the process of moving them in/out of the building? Given the purported rigid war machine schedule at the school, it would give McKenzie lilliputian opportunity to stage such an image (much less the permission to play with school belongings). Co-ordinate to Trennert, "…everything operated on a schedule, and the campus resembled an ground forces kicking camp. In contrast to the leisurely pace of reservation life, children were required to study, clean their rooms, slumber, and eat at specific times. Sundays were devoted to discipline" ([12], p. 117). So information technology seems as though the photograph was made surreptitiously, by finding some time to steal abroad and create the portrait. It is also possible that school administrators did not have a problem with the photograph being taken if they thought information technology supported their civilizing and modernizing goals. If this were truthful, and so McKenzie's actions get an embodied act of visual sovereignty. He is fashioning himself as an ideal educatee of their making, nevertheless he is already planning to utilize the noesis he caused to preserve and continue his Native language (which coincidentally was prohibited to be spoken at school). By authoring his self-portrait in this style, he performs the act of visual sovereignty while simultaneously making a broader argument for cultural revitalization and self-determination.

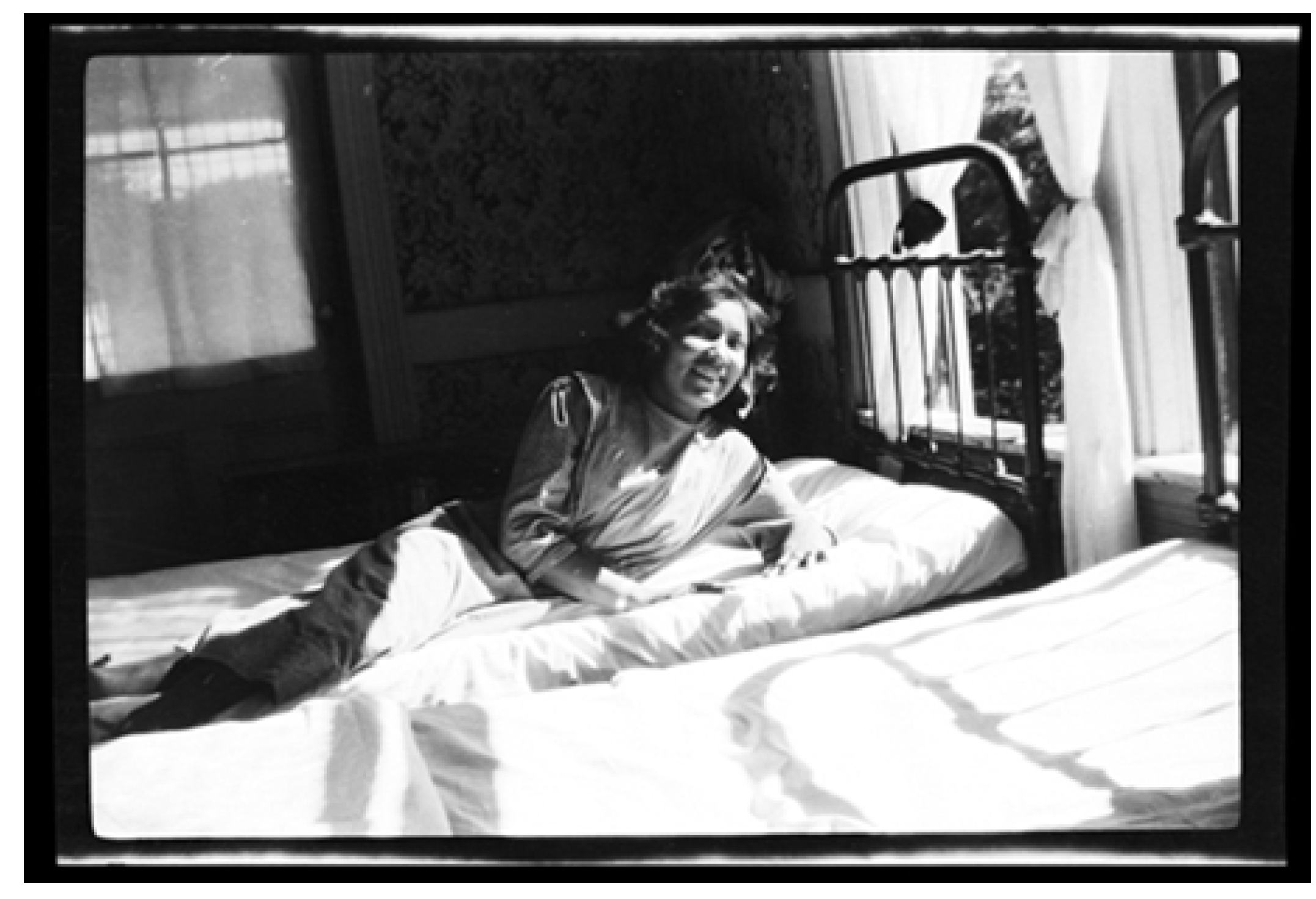

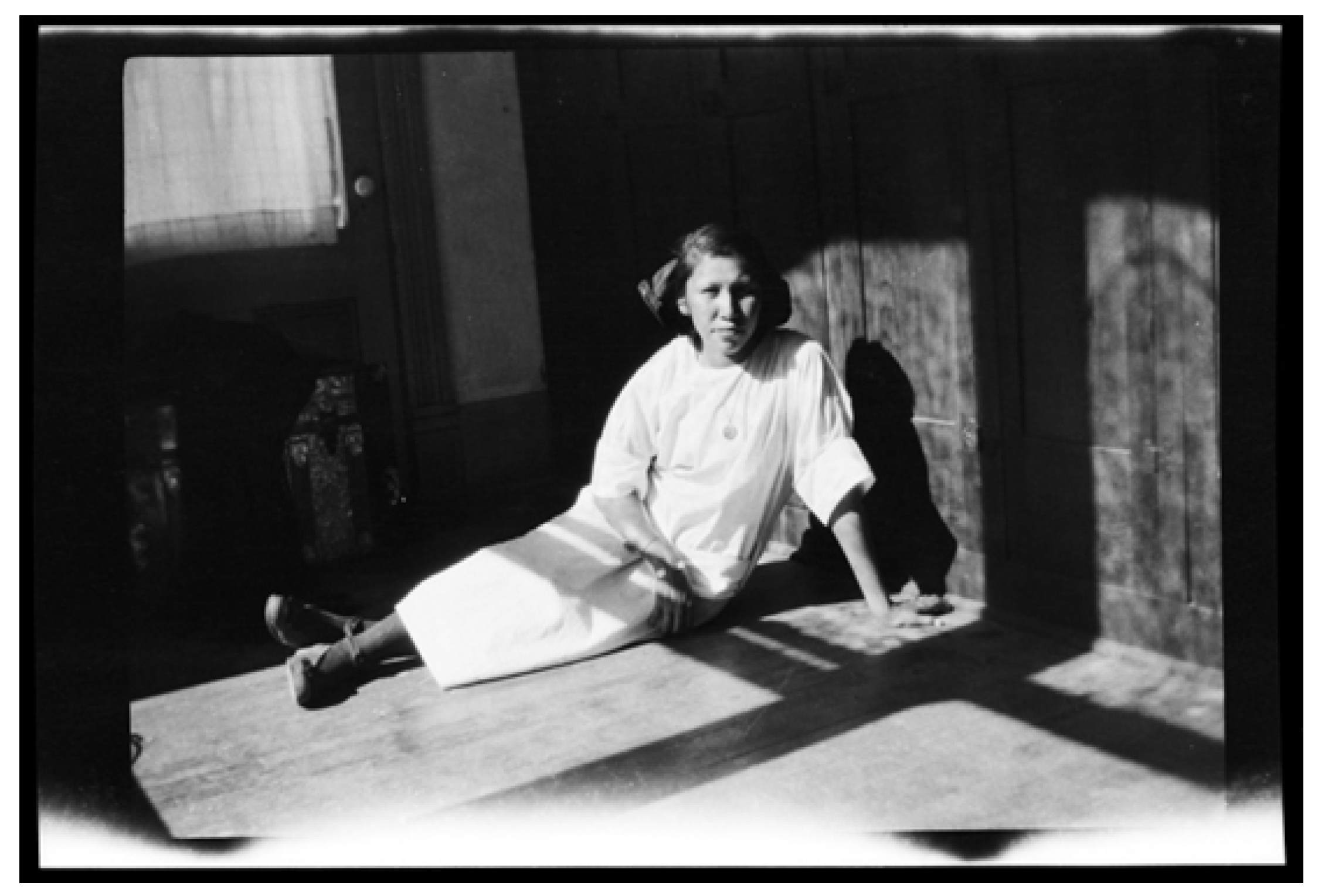

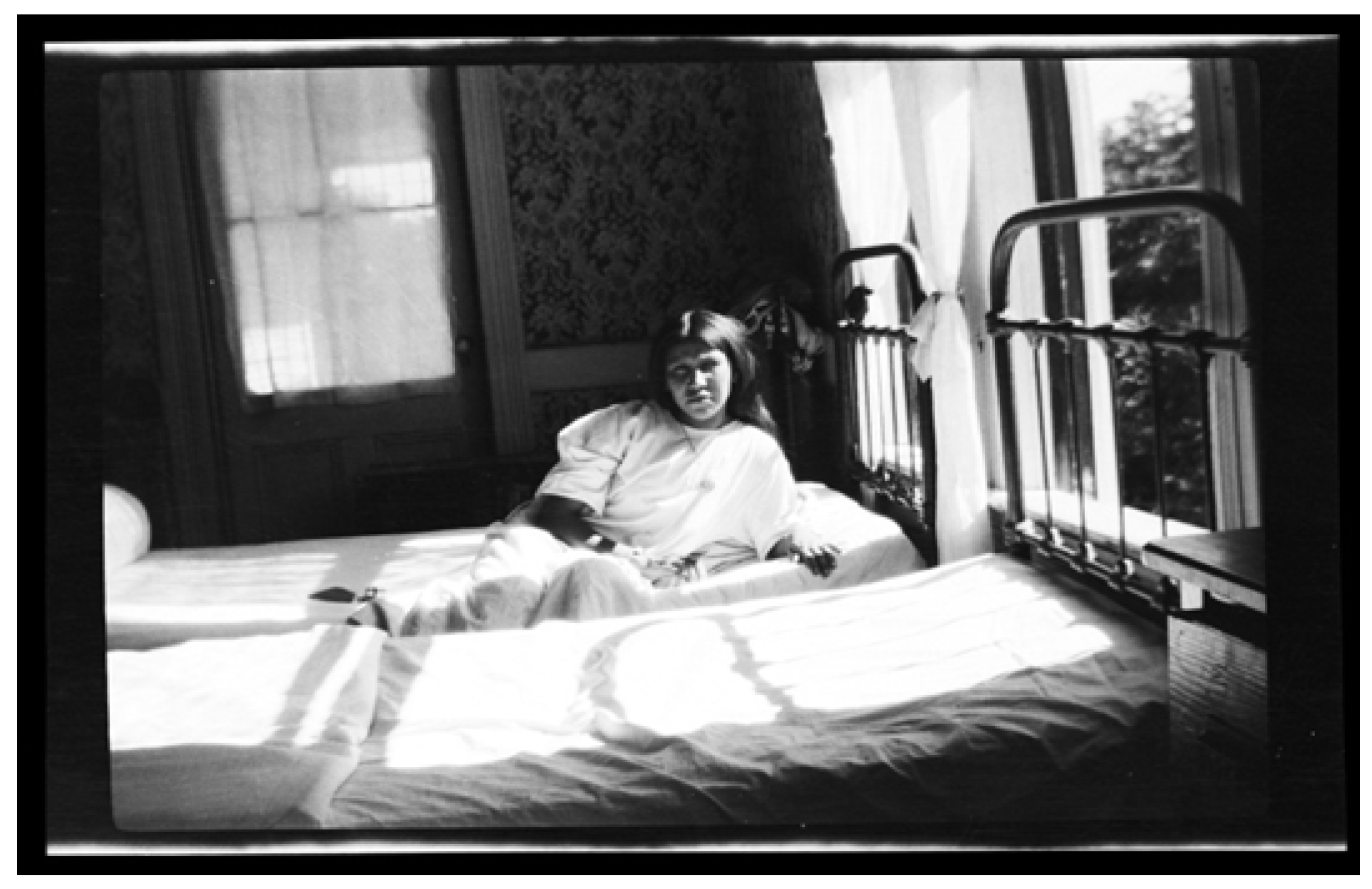

four. Nettie Odlety, Lensman

Nettie Odlety purchased a photographic camera at the same time as Parker McKenzie, and with it, she photographed what is perhaps the only existing vernacular imagery inside the girls' dormitory walls. In a series of snapshots (Effigy 14, Figure fifteen, Figure 16 and Figure 17) taken erstwhile between 1915 and 1916, Odlety and her friend, Lucy Sumpty, took turns being lensman and subject. Every bit the girls alternate posing on the ground and lounging on a bed, the afternoon sun comes through the dorm room windows and illuminates the scene. Upon closer inspection, it appears as though they are mimicking each other's pose—from the vantage bespeak every bit photographer to the body positioning as subject area.

Effigy xiv. Nettie Odlety, Within the Girls' Dormitory—Phoenix Indian Boarding Schoolhouse, c. 1915. Parker McKenzie Collection. Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Club.

Figure 14. Nettie Odlety, Inside the Girls' Dormitory—Phoenix Indian Boarding Schoolhouse, c. 1915. Parker McKenzie Collection. Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Figure xv. Nettie Odlety, Inside the Girls' Dormitory—Phoenix Indian Boarding Schoolhouse, c. 1915. Parker McKenzie Drove. Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Figure 15. Nettie Odlety, Within the Girls' Dormitory—Phoenix Indian Boarding School, c. 1915. Parker McKenzie Collection. Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Social club.

Figure 16. Lucy Sumpty, Inside the Girls' Dormitory—Phoenix Indian Boarding School, c. 1915. Parker McKenzie Collection. Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Guild.

Effigy sixteen. Lucy Sumpty, Within the Girls' Dormitory—Phoenix Indian Boarding School, c. 1915. Parker McKenzie Collection. Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Figure 17. Lucy Sumpty, Inside the Girls' Dormitory—Phoenix Indian Boarding School, c. 1915. Parker McKenzie Collection. Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Effigy 17. Lucy Sumpty, Inside the Girls' Dormitory—Phoenix Indian Boarding School, c. 1915. Parker McKenzie Collection. Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Gild.

Formerly subjects of the Western gaze, these women take taken the camera into their own easily, and they are condign agents, non objects of photography. With their alternate snapshots, the girls demonstrate their burgeoning visual language of self-fashioning, and in doing so they are "stretching the boundaries of Indigenous representation through the deployment of visual sovereignty" ([36], p. 220). They seem to be taking their time modeling for the camera, despite the "consummate surveillance of and control over female person Indian bodies within the schools" ([23], p. 96). However, this example of private indulgence was not necessarily an uncommon occurrence. Some female students reportedly "managed to smuggle bean sandwiches out of the kitchen, tell stories after lights out, fifty-fifty concur peyote meetings in their dorm rooms. Private moments knitted students together in shared joy, shared language, or shared mischief" ([11], p. 48). The photographs seem to dorsum upwards the thought that the dorm rooms were not only a place for sleeping, merely a infinite where friendships were formed and, in this case, recorded.

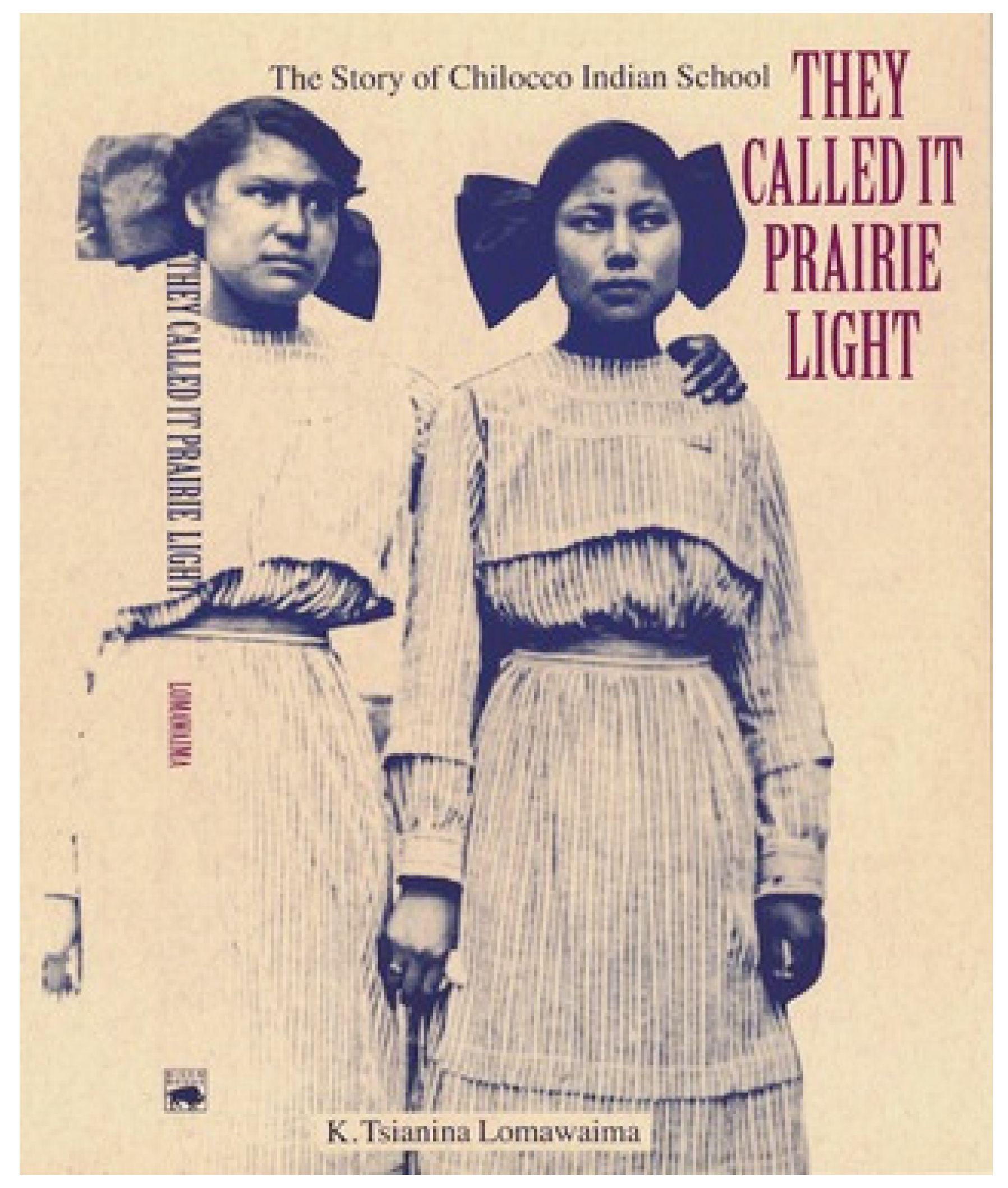

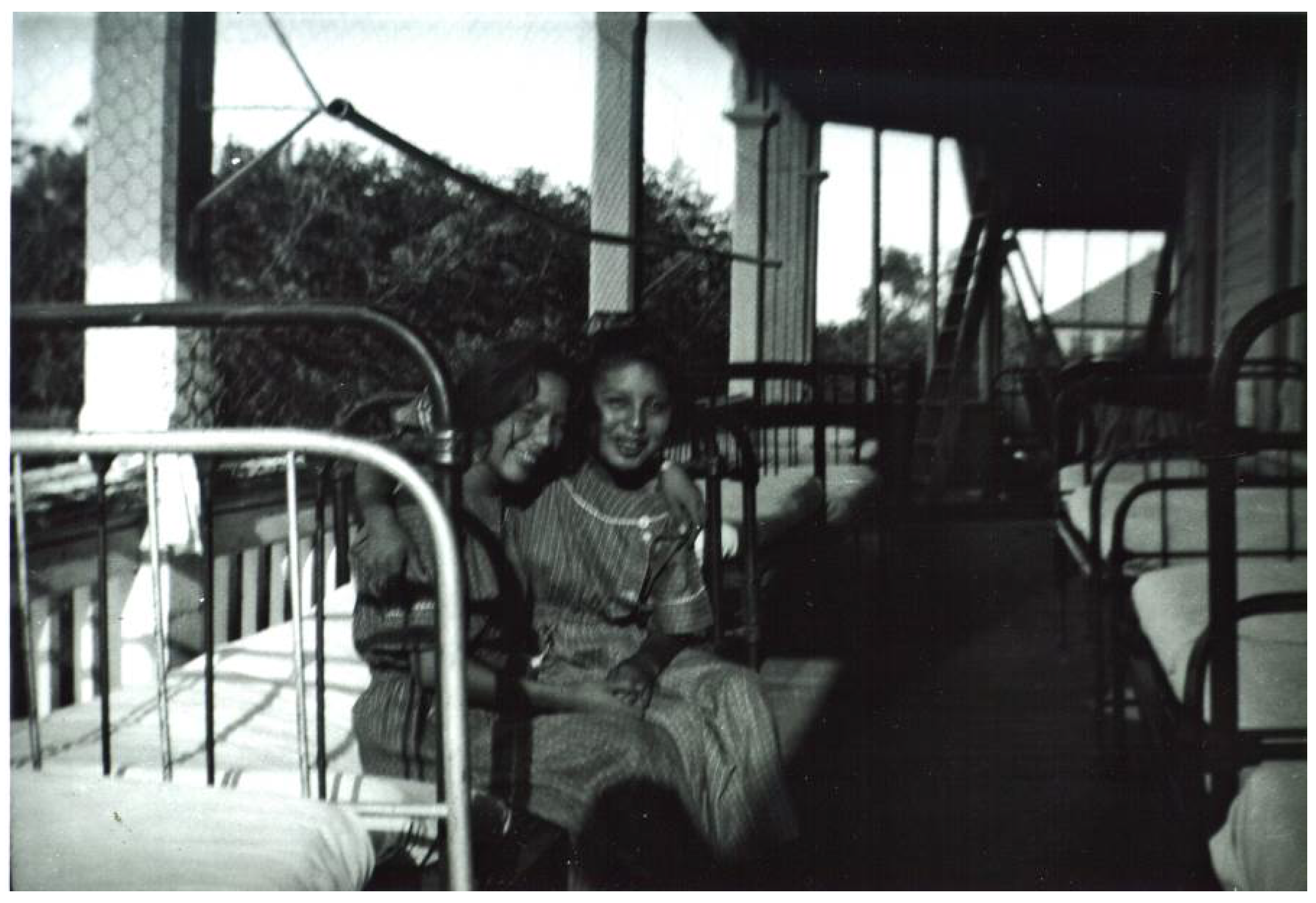

An all-encompassing study of the female boarding school experience was undertaken by K. Tsianina Lomawaima who found that "a circuitous network of bonds and divisions that simultaneously bound and segmented the large student population. Girls united in groups formed by dorm-room association, shared hometowns, native language ties, company or piece of work item assignments, or similar personality" ([23], p. 97). Along with this statement, she provides a photo of two Chilocco girls in schoolhouse dress, dated to 1914, and uses this image for her book cover (Figure 18) [23]. In the photograph, the girls stand stiffly and unsmiling as they pose for an official school photographer. One girl has an arm around the other girl's shoulders, but information technology looks forced and unnatural. This is in stark comparing to a photograph taken one year later (1915) by Nettie Odlety of her roommates, Deoma Doyebi and Ethel Roberts (Figure 19).

Effigy 18. Book embrace for They Chosen It Prairie Lite by K. Tsianina Lomawaima.

Effigy xviii. Book cover for They Called It Prairie Light by Thousand. Tsianina Lomawaima.

Effigy 19. Deoma Doyebi (Kiowa) and Ethel Roberts (Wichita), ca. 1916. Photograph by Nettie Odlety, Parker McKenzie Collection. Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Figure 19. Deoma Doyebi (Kiowa) and Ethel Roberts (Wichita), ca. 1916. Photograph by Nettie Odlety, Parker McKenzie Collection. Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Odlety captures her friends in a moment of camaraderie with their arms looped around each other'due south shoulders as they enthusiastically smiling towards the photographic camera. While these two photographs take like discipline matter, it is articulate that authorship can affect the fashion in which the subjects are represented. Equally Theresa Harlan contends, "the camera technique and even the choice of subject field may be similar, but the involvement and the handling of the resulting works is not" ([39], p. seven). There is an obvious comfort level when beingness photographed past a familiar person—people tend to allow downwardly their guard and the resulting image is ordinarily closer to the actual graphic symbol of the person(southward) being represented. This is certainly true regarding these two images. The girls in the officially-produced image may be friends, but they look uncomfortable expressing themselves in front of the lensman. Instead, they stand rigidly and display the formal public image (of proper young ladies) expected of them. Conversely, the photo taken by Odlety seems to be a more accurate representation of the interpersonal relationships forged between her classmates and tribal members. According to Tuscarora artist and scholar Jolene Rickard, "photographs fabricated by ethnic makers are the documentation of our sovereignty, both politically and spiritually…the images are all connected, circling in always-sprawling spirals the terms of our experiences equally human being beings...hooking memories through fourth dimension" ([31], p. 54). What she describes is an of import aspect of indigenous visual heritage, the connections that create a dynamic, tangible link between the past, nowadays, and time to come.

5. Conclusions

Educatee snapshots are disregarded master sources in the documentation of the American Indian boarding school experience. As photo historian Graham Clarke writes,

The snapshot remains undervalued every bit a form of photography, defective the distinctiveness and substance of images produced past the professional lensman. And nevertheless, the snapshot is the footing of most people'south feel of the photograph; both of taking photographs and of saturating themselves inside a photographic history of their own making. The snapshot has transcended its office as a photograph and answers a new set up of needs, with a new kind of significance.

([40], p. 218)

The Native-produced snapshots express multiple realities and illuminate stories of resistance, endurance, and continuing presence [41,42,43]. The visual sovereignty enacted past these photographers provides an culling approach to the visual history of American Indian Boarding school experience. Equally Michelle Raheja states, these type of Native image-makers, "operate as technological brokers and autoethnographers of sorts, moving betwixt the community from which they hail and the Western globe and its overdetermined images of ethnic people" ([36], p. 219). This is where McKenzie's photographic drove is most valuable. Unlike official school photography, which ofttimes has an calendar to provide bear witness of "progress," his collection functions as a corrective visual narrative to combat decades of Western cultural hegemony. For example, the smiling face of a school sweetheart (Effigy 20) is an image that is but non institute in the officially-produced collections.

Figure 20. Nettie Odlety, ca. 1916. Parker McKenzie Collection. Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Gild.

Figure twenty. Nettie Odlety, ca. 1916. Parker McKenzie Collection. Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Some scholars have taken the approach that boarding schools were created to obliterate tribal identity, and that officially-produced photographs reflect this fact [8,9,10]. Notwithstanding, as historian Clyde Ellis states, "every bit with then many other culturally loaded encounters, Indian educational activity could be—and ofttimes was—used by Native people to serve multiple ends that included maintaining identity. That Indian people used the schools to accommodate their needs and purposes is an important consideration, for it raises the oftentimes-overlooked notion of bureau" ([24], p. 67). This concept of agency has largely been absent-minded in the visual history of the boarding schoolhouse feel. By visually recording their ain experiences, these marginalized students subverted the otherwise oppressive institution and claimed parts of it for themselves. In doing so, they created a counter-annal that documented their visual sovereignty.

Acknowledgements

Firstly, the author would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers too as the editor for their constructive comments. Next, the author extends appreciation to Chester Cowan, Bill Welge, and the unabridged staff at the Oklahoma Historical Club for their kindness and assistance with the Parker McKenzie Drove. In addition, the author is indebted to Clyde Ellis for sharing his interview notes from his meetings with Parker McKenzie. Finally, and near importantly, thank you lot to Parker McKenzie for sharing your photographs with the public.

Conflicts of Interest

The writer declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Michael Cooper. Indian School: Teaching the White Man'southward Mode. New York: Clarion, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kathleen McWeeney, Laura Turner, Molly Fraust, Stephanie Latini, Kathryn Moyer, and Antonia Valdes-Dapena. Visualizing a Mission: Artifacts and Imagery of the Carlisle Indian School, 1879–1918. Edited by Philip Earenfight. Carlisle: Trout Gallery, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Eric Margolis. "Looking at Discipline, Looking at Labour: Photographic Representations of Indian Boarding Schools." Visual Studies xix (2004): 72–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eric Margolis, and Jeremy Rowe. "Images of Absorption: Photographs of Indian schools in Arizona." History of Education 33 (2004): 199–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonna Malmsheimer. "'Imitation White Homo': Images of Transformation at the Carlisle Indian School." Studies in Visual Communication 11 (1984): 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amelia Katanski. Learning to Write "Indian": The Boarding Schoolhouse Experience and American Indian Literature. Norman: University of Oklahoma Printing, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Michael Coleman. American Indian Children at Schoolhouse, 1850–1930. Jackson: University Printing of Mississippi, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- David Wallace Adams. Pedagogy for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Feel, 1875–1928. Lawrence: University Printing of Kansas, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ward Churchill. Kill the Indian, Save the Man: The Genocidal Impact of American Indian Residential Schools. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kay Porterfield. "Brainwashing and Boarding Schools: Undoing the Shameful Legacy." Available online: http://www.kporterfield.com/aicttw/articles/boardingschool.html (accessed on 28 July 2015).

- Frank Goodyear Jr., Brenda Child, K. Tsianina Lomawaima, Margaret Archuleta, Nora Naranjo-Morse, Louise Erdrich, Oskiniko Larry Loyie, Rayna Green, John Troutman, John Flower, and et al. Away From Home: American Indian Boarding School Experiences 1879–2000. Edited by Margaret Archuleta, Brenda Kid and M. Tsianina Lomawaima. Phoenix: Heard Museum, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Robert Trennert. The Phoenix Indian School: Forced Assimilation in Arizona, 1891–1935. Norman: Academy of Oklahoma, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes Peter Mauro. The Art of Americanization at the Carlisle Indian School. Albuquerque: University of New United mexican states Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- John Milloy. A National Criminal offence: The Canadian Government and the Residential Schoolhouse Organisation 1879 to 1986. Winnipeg: Manitoba University Printing, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Celia Haig-Brownish. Resistance and Renewal: Surviving the Indian Residential Schoolhouse. Vancouver: Arsenal Lurid Press, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- James Miller. Shingwauk's Vision: A History of Native Residential Schools. Toronto: Academy of Toronto Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Holly Littlefield. Children of the Indian Boarding Schools: Picture the American By. Minneapolis: Carolrhoda Books, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey Montez de Oca, and Jose Prado. "Visualizing Humanitarian Colonialism: Photographs from the Thomas Indian School." American Behavioral Scientist 58 (2014): 145–70. [Google Scholar]

- Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie. "Compensating Imbalances." Exposure 29 (1993): 29–30. [Google Scholar]

- Don Alexander. "Prison house of Images: Seizing the Means of Representation." Fuse Magazine, Feb/March 1986, 45–46. [Google Scholar]

- John Bloom. To Show What an Indian Can Exercise: Sports at Native American Boarding Schools. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Clyde Ellis. To Alter Them Forever: Indian Education at the Rainy Mountain Boarding Schoolhouse, 1893–1920. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- M. Tsianina Lomawaima. They Called It Prairie Light: The Story of Chilocco Indian Schoolhouse. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- David Wallace Adams, Clyde Ellis, Jacqueline Fearfulness-Segal, Barbara Landis, Scott Riney, Tanya Rathbun, Katrina Paxton, Margaret Connell Szasz, Margaret Jacobs, Patricia Dixon, and et al. Boarding School Blues: Revisiting American Indian Educational Experiences. Edited by Clifford Trafzer, Jean Keller and Lorene Sisquoc. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ester Horne, and Emerge McBeth. Essie's Story: The Life and Legacy of a Shoshone Teacher. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Printing, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. The Survivors Speak: A Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Winnipeg: Truth and Reconciliation Committee of Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jo-Anne Driessens, Michael Aird, Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie, Roslyn Poignant, James Faris, Morris Low, Nicholas Peterson, Christopher Wright, Deborah Poole, Christopher Pinney, and et al. Photography'southward Other Histories. Edited past Christopher Pinney and Nicolas Petersen. Durham: Duke University Printing, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie. The Oxford Companion to the Photograph. Edited by Robin Lenman. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Linda Witmer. The Indian Industrial Schoolhouse, Carlisle, Pennsylvania, 1879–1918. Carlisle: Cumberland County Historical Order, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Parker McKenzie. Interview by Clyde Ellis, 1 August 1990, Unpublished Transcript (Courtesy of Clyde Ellis).

- Paul Chaat Smith, Northward. Scott Momaday, Theresa Harlan, Zig Jackson, James Luna, Jolene Rickard, Leslie Marmon Silko, Linda Hogan, Luci Tapahonso, Larry McNeil, and et al. Potent Hearts: Native American Visions and Voices. Edited by Peggy Roalf. New York: Aperture, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Donald Fixico. The American Indian Heed in a Linear World: American Indian Studies and Traditional Knowledge. New York: Routledge, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Suzanne Benally, Jimmie Durham, Rayna Green, Joy Harjo, Gerald McMaster, Jolene Rickard, Ramona Sakiestewa, David Seals, Paul Chaat Smith, Jaune Quick-To-Run into-Smith, and et al. Partial Recollect: With Essays on Photographs of Native North Americans. Edited by Lucy Lippard. New York: The New Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Parker McKenzie, and Parker McKenzie Collection, Oklahoma Historical Lodge. Personal correspondence.

- Michael Katakis, Gerald Vizenor, and Robert Preucel. Excavating Voices: Listening to Photographs of Native Americans. Edited by Michael Katakis. Philadelphia: Academy of Pennsylvania Museum of Archeology and Anthropology, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Michelle Raheja. Reservation Reelism: Redfacing, Visual Sovereignty, and Representations of Native Americans in Motion-picture show. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Printing, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Erving Goffman. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Doubleday, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Richard Brilliant. Portraiture. London: Reaktion, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Theresa Harlan. "Bulletin Carriers: Native Photographic Messages." Views: The Journal of Photography in New England 13–14 (1993): iii–7. [Google Scholar]

- Graham Clarke. The Photograph. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Jane Carmichael, Henrietta Lidchi, Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie, Veronica Passalacqua, Amalia Pistilli Conrad, Gwyneria Issac, Mique'l Icesis Askren, and Larry McNeil. Visual Currencies: Reflections on Native Photography. Edited by Henrietta Lidchi and Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie. Edinburgh: National Museums Scotland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mique'fifty Icesis Askren, Joan Jensen, Teo Allain Chambi, Andrés Garay Albújar, Theresa Harlan, Duncan Aguilar, Sama Alshaibi, Pena Bonita, Rosalie Favell, Shan Goshorn, and et al. Our People, Our Land, Our Images: International Indigenous Photographers. Edited past Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie and Veronica Passalacqua. Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- George Horse Capture, Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie, Jolene Rickard, Mick Gidley, Paula Richardson Fleming, Elizabeth Edwards, Colin Taylor, Benedetti Cestelli Guidi, and Theresa Harlan. Native Nations: Journeys in American Photography. Edited by Jane Alison. London: Barbican Art Gallery, 1998. [Google Scholar]

-

1 The utilize of these photographs is not limited to these scholars. I have plant that media outlets (including PBS and NPR), museums (such equally the Smithsonian Institution), and diverse websites (including Grand-12 common core instruction manuals) have also employed the official school photographs in this manner as well.

-

2 The forced absorption era originates with the establishment of Carlisle in 1879 (which became the model for the other 26 federally funded off-reservation boarding schools), and concludes afterwards the Meriam Report of 1928 that exposed failures in the boarding school system. The U.S. Government instigated policy changes culminating in the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, which reversed the assimilationist agenda and ushered in the Progressive era. Near photographs employed for boarding school boosterism were created in the forced assimilation era. For a word of Progressive era boarding school photographs, run into Montez de Oca and Prado [eighteen].

-

3 Afterward graduating from Carlisle in 1896, Leslie returned domicile to the Pacific Northwest where he became a professional photographer. The Indian Helper reported that the alumnus was "doing well in his photography business. In three weeks he took in $40.00" (equally cited in [13], p. 125). An analysis of Leslie's professional career would be interesting, but falls exterior the purview of this article.

-

iv Parker McKenzie admitted that he collected, merely did non accept any photographs while attending Rainy Mount. I was unable to locate the identity of Rainy Mountain official schoolhouse lensman, so it may have been an itinerant photographer or, most likely, one of the staff.

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Artistic Eatables Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0787/4/4/726/htm

0 Response to "Mauro Hayes Peter The Art of Americanization at the Carlisle Indian School Pdf"

Postar um comentário